USA Coin Album: It’s the Law! Lesser-known Passages Relating to United States Coinage—Part Five

Posted on 2/13/2018

This figure was selected to keep the coins, which had limited legal tender value, from becoming a redundant nuisance in circulation. Congress considered the specified figure quite sufficient for the economy of the time. In fact, the falling price of silver returned so many formerly exiled coins to domestic circulation in 1876-77 that it became necessary to suspend the coining of fractional silver in 1878 to enforce the $50 million limit. Dime production returned to normal levels in 1882, but quarters and halves were struck mostly in very small numbers as late as 1890.

In the meantime, however, the United States had grown so rapidly in its production and wealth that this limit was a handicap to the booming economy of America's Gilded Age. As a result, the Treasury quietly disregarded the legal cap and produced as many fractional coins as were needed over the next 15 years. It was not until 1906 that this embarrassing situation was properly addressed—the US attorney general ruled that the broader Mint Act of 1873 took precedence over its annoying 1876 codicil, and he waived the $50 million limit.

The 1876 law had limited the legal tender value of fractional silver coins to just $5 in any one transaction, but the Act of June 9, 1879 raised this figure to $10. It also made the coins redeemable at the Treasury and its branches for gold coin when presented in sums not less than $20. This was a tacit acknowledgment that gold coins were finally circulating at par with other forms of United States coins and notes, the stated goal of the Specie Resumption Act of January 14, 1875. For the first time since 1861, all was well with America's money—with one glaring exception.

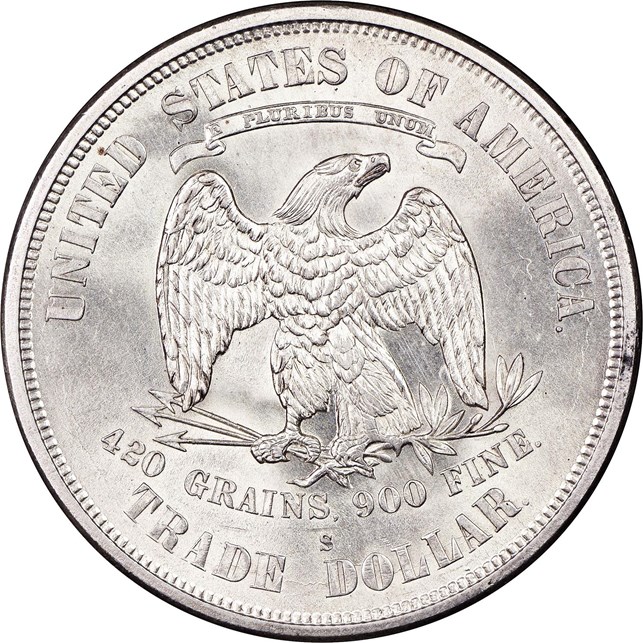

The trade dollar hadn't been produced for export since early in 1878, though proofs were struck annually for collectors as late as 1883. Even so, the coins were common as ever in domestic circulation. Legally worth only their silver value, they were nonetheless forced upon the unwary (and those not in a position to refuse them) at their nominal face value of one dollar. Retailers sometimes grudgingly accepted them as payment, rather than lose business. Banks refused them for deposits, so store owners then had to sell them at a discount to brokers. The latter dispensed them at a profit (though still less than face value) to factory owners and other large employers, who paid them out at par. In this manner, the misery never seemed to end. Ultimately, a law passed February 19, 1887 made the Treasury liable to redeem trade dollars at face value, sustaining a loss in the process. The curious provision of this law, however, is that the coins for redemption could not be "defaced, mutilated, or stamped..." Thus it is that so many chop-marked trade dollars have survived, while most clean examples went to the melting pot.

With the nation's coinage needs being met handily by 1890, there should have been no incentive for additional tweaking by Congress, yet political interests dictated otherwise. The Bland-Allison Act of February 28, 1878 had authorized many millions of unneeded silver dollars, theoretically boosting the value of silver in the process. Its price, however, continued a steady decline, leaving the silver dollar worth significantly less than the gold dollar in bullion value.

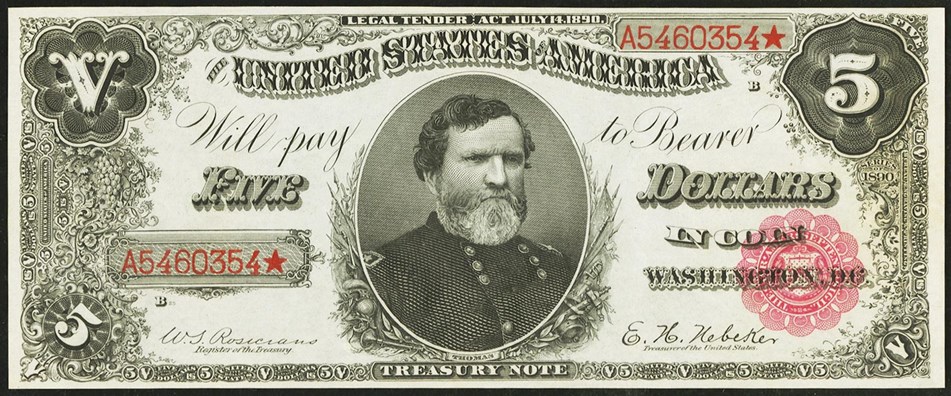

Seeking still further relief, western silver mining interests got Congress to pass a supplemental law July 14, 1890 that called for the coining of even greater numbers of silver dollars. Bullion purchases would be paid for with a new series of currency, Treasury Notes. These notes were themselves made redeemable in either gold or silver coin, at the discretion of the treasury secretary, as it was the "established policy of the United States to maintain the two metals on a parity with each other..." A complete denial of reality, this clause led to a near depletion of the nation's gold reserves, since Treasury Notes issued in exchange for silver bullion were almost immediately redeemed by their holders in gold coin. This catastrophic law was finally repealed in 1893, by which time the nation was slipping into a severe economic depression.

In keeping with the theme of this series of columns, there is, of course, an odd and little known provision within the 1890 law. The coining of silver dollars was to continue as provided under the terms of this act until July 1, 1891. At that point, the silver bullion purchased was to made be into silver dollars only to the amount needed to redeem the Treasury Notes! Of course, no one wanted to exchange the notes for silver dollars, when the profit was in trading them for gold coin, so this clause was just a cruel joke on the American people. It's no wonder that the issue of gold versus silver became such a major debate of the 1896 and 1900 presidential elections.

David W. Lange's column, “USA Coin Album,” appears monthly in The Numismatist, the official publication of the American Numismatic Association.

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!